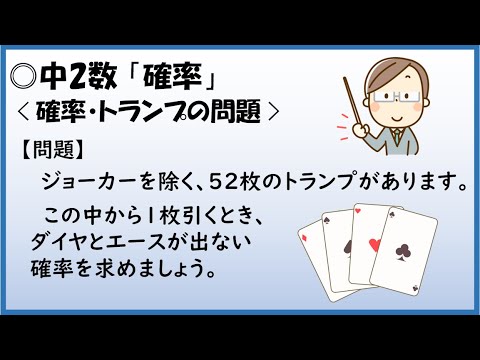

私が強いられた(認めざるをえなくなった)もうひとつの結論は、もし我々(人間)が(自分達が)ただ経験でき、立証(検証)できるものみを知る(それ以外知ることができない)としたら、 科学だけでなく、誰もがまじめには疑うことのない多くの知識が不可能になるということ(結論)である。 経験というものがいままであまりにも強調されすぎており、従って、哲学としての経験論は重大な制限を受けなければならない(must be subjected to)と私は感じた。 私は、当初、そこに含まれている問題の広範さと多様さ(multiplicity 多重性)に戸惑った。 私は、非論証的推論の本質はその(非論証的推論の)結論にただ確率(蓋然性)のみを与えることにあると理解し、まず確率(蓋然性)の探求から着手するのが賢明だろうと考えた。特に、この確率(蓋然性)の問題については、不確実性の大海に浮ぶ筏(raft いかだ)のような(に似た)一群の積極的知識が存在していた(からである)。私数カ月間、私は確率の微積分(calculus)とその応用について研究を行った。確率には二種類あり、一つは統計によって例示され、他は疑わしさ(doubtfulness)によって例示される。 理論家のなかにはこれらの一方だけで事がすむ(問題を処理できる)と考える人達がおり、また、もう一方だけで事がすむ(処理できる)と考える理論家もいた。通常の解釈によると、数学の微積分は統計的な種類の確率を取り扱う。たとえば、トランプの箱には52枚のカードがあるので、その中から一枚をランダムに(無作為に)引けば、そのカードがダイヤの7である見込み(チャンス)は52分の一である。カードをランダムに(無作為に)非常に多くの回数引けば、ダイヤの7は およそ五十二回ごとに一回出てくるだろうということが、決定的な証拠なしに、通常、仮定(想定)されてい る。 確率の問題はもともと貴族が運が左右するゲーム(games of chance)について抱いた関心から生れた。 貴族たちは、賭けごとを金がかかるものよりも儲かるものにするような理論を考え出させようとして、数学者を雇った。数学者は興味ある多くの著作(業績)を生み出したが、(彼らの)雇い主を富ませたようには見えない。

Chapter 16: Non-Demonstrative Inference , n.2

Another conclusion which was forced upon me was that not only science, but a great deal that no one sincerely doubts to be knowledge, is impossible if we only know what can be experienced and verified. I felt that much too much emphasis had been laid upon experience, and that, therefore, empiricism as a philosophy must be subjected to important limitations. I was at first bewildered by the vastness and multiplicity of the problems involved. Seeing that it is of the essence of non-demonstrative inference to confer only probability upon its conclusions, I thought it prudent to begin with an investigation of probability, especially as, on this subject, there existed a body of positive knowledge floating like a raft upon the great ocean of uncertainty. For some months, I studied the calculus of probability and its applications. There are two kinds of probability, of which one is exemplified by statistics, and the other by doubtfulness. Some theorists have thought that they could do with only one of these, and some have thought that they could do with only the other. The mathematical calculus, as usually interpreted, is concerned with the statistical kind of probability. There are fifty-two cards in a pack, and therefore, if you draw a card at random, the chance that it will be the seven of diamonds is one in fifty-two. It is generally assumed, without conclusive evidence, that, if you drew cards at random a great many times, the seven of diamonds would appear about once in every fifty-two times. The subject of probability owed its origin to the interest of aristocrats in games of chance. They hired mathematicians to work out systems which should make gambling lucrative rather than expensive. The mathematicians produced a lot of interesting work, but it does not appear to have enriched their employers. Source: My Philosophical Development, 1959, by Bertrand Russell More info. https://russell-j.com/beginner/BR_MPD_16-010.HTM